Helen Bailey has written research papers and chapters in scientific books about her marine research.

When it came to her work on sea turtle hatchlings, however, she decided to direct her research at a new audience—children.

Bailey, an associate research professor at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science’s Chesapeake Biological Laboratory, partnered with her long-term turtle research collaborator, George Shillinger, then executive director of the non-profit conservation group The Leatherback Trust to write a children’s book. The book is titled “The Grande Turtle Adventure.”

The illustrated tale, told in rhyme, simplifies years of research about where leatherback sea turtles go after they hatch. She wanted to teach kids about some of the human-caused dangers these turtles face. One page, for example, highlights the difficulty turtles have differentiating between the jellyfish they eat and plastic bags littered in the ocean.

The details behind the adventures of main characters Laurie and Tica are based on a research project that Shillinger led called “The Lost Years.”

The Lost Years project began in 2010 and Bailey, who had just arrived at the UMCES’ Chesapeake Biological Laboratory, joined the team along with her graduate student Aimee Hoover.

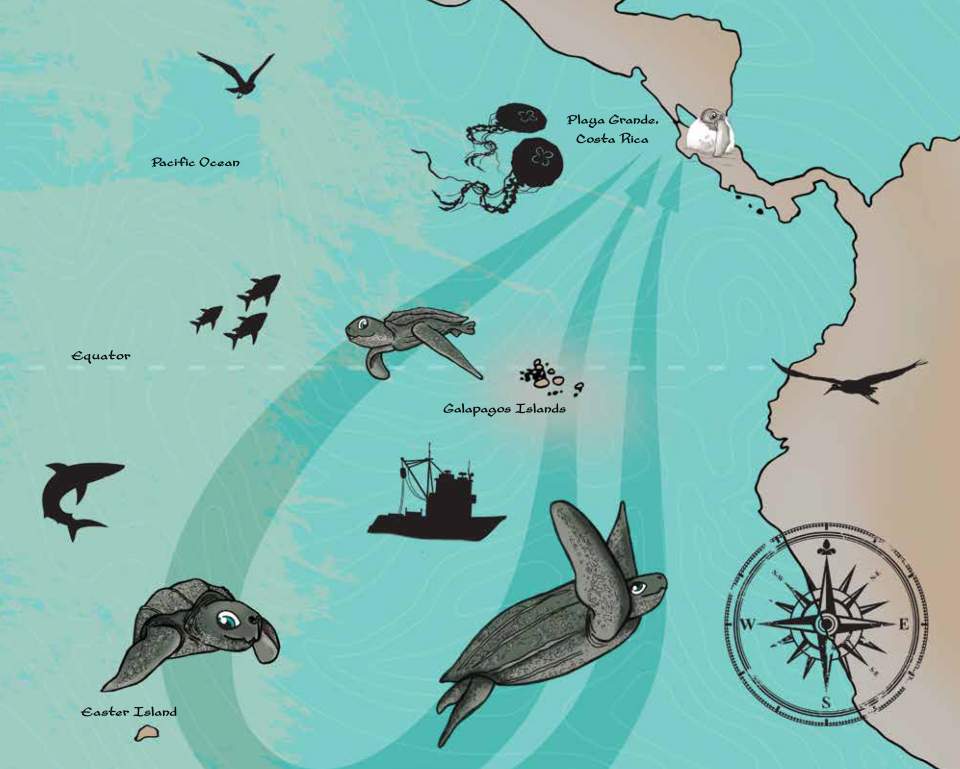

To study the leatherback’s “lost years,” the scientists used acoustic tags that gave off sound signals to track the hatchings from Playa Grande, Costa Rica.

Their goal was to better understand the leatherbacks’ migration habitats between birth and adulthood, when they return to their nesting beach to lay eggs. The stretch of lost time can last up to 25 years.

“There’s been this missing piece of what happens to the young turtles and how that shapes their migration and dispersal patterns as adults,” Bailey said.

A plummeting population of leatherback turtles in the Eastern Pacific Ocean was motivating the researchers to learn more about the turtles. There had been thousands of adult leatherbacks returning to nest on Playa Grande each year, but this year only 11 came back, Shillinger said.

We really wanted to do a children’s version of our research to help people understand, both through the children and their parents and teachers, what’s going on, why these animals are at risk, and what we can do.

The Leatherback Trust has been working to protect leatherback turtles—the world’s largest turtle—and other sea turtles from extinction. It specifically has worked to protect turtles at Playa Grande where increasing development has posed a threat to the turtles, Shillinger said.

Too many lights can confuse the turtles. Construction causes erosion, reducing tree cover and altering the shape of the shoreline as well as sand available for nesting, he said.

Many years of rampant poaching, prior to the creation of the Playa Grande National Park in 1991, left a gap in the number hatching, as well, Shillinger said.

“Our hope is eventually they will recover, but it could take a really long time,” Bailey said.

With their research, the scientists could help propose changes in human activity that affects the turtles, such as where fishing boats drop their lines and nets. Bailey and Shillinger then wanted to take their work a step further to really raise awareness about this vulnerable species of turtle.

“There’s a limited audience to scientific papers and it occurred to us, we’re working on hatchling turtles, maybe we needed to work on 'hatchling' people, as well,” Bailey said. “We really wanted to do a children’s version of our research to help people understand, both through the children and their parents and teachers, what’s going on, why these animals are at risk, and what we can do.”

Bailey didn’t just use her research skills to tell the story. With two children of her own, she had practice reading Julia Donaldson’s “Room on the Broom” aloud and wanted to give her own book a similar rhythm.

The story of Laurie and Tica begins on a tropical beach in Playa Grande and includes a visit past the Galapagos Islands and Easter Island, mirroring the scientists research from “The Lost Years” project.

Bailey and Shillinger used place names to focus specifically on the Eastern Pacific leatherback. That set it apart from other children’s conservation books, but “did add to the challenge of trying to make it rhyme,” Bailey said.

The book took about two years to put together with Tracy Dorsey, Bailey’s sister-in-law and a graphic artist, joining the team to illustrate the book, while Susana Chanfón Kung translated it into Spanish. The authors, illustrator, and translator dedicated the book to their own “favorite little hatchings,” their children, and in memory of Laurie Spotila, the late wife of Jim Spotila, the Trust’s founder.

Autographed copies of the book are on sale for $20 each (cash or personal check only) in Chesapeake Biological Laboratory’s Visitor Center in Solomons, Maryland. All of the proceeds made from the sale of the book will support sea turtle research and conservation through The Leatherback Trust.