Hali Kilbourne thanks the National Science Foundation for funding and with their continued support we hope to be back for more next year!

Some time between 1200 and 1450--when the Black Plague was ravaging Europe, Geoffrey Chaucer was writing his Canterbury Tales, and Marco Polo was traveling the world--a giant tsunami washed part of a reef onto the beach in what is now the British Virgin Islands.

Those corals are still there, and hold the key to what was going on with the climate during a key period between one of the warmest known eras on our planet and the coldest phase since the last Ice Age.

Paleoclimatologist Hali Kilbourne and geochemist Johan Schijf of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science's Chesapeake Biological Laboratory are there right now to sample the corals on the beach to reconstruct the climate of the region at that time.

Follow their 2013 research cruise in Anegada here:

March 12 & 13

Hali Kilbourne and Johan Schijf arrived in the British Virgin Islands (BVI) on Tuesday. We flew from Baltimore to San Juan, PR, and from there took a small Cessna twin-engine plane to Tortola, the main island of the BVI. Kelly got to sit in the co-pilot seat next to the pilot and I sat directly behind her. We had a beautiful view of the US Virgin Islands, which are immediately east of Puerto Rico.

On Tortola, a taxi took us to our hotel in Road Town, the main settlement (see photo). Then all we had to do was wait for our equipment and the other team members. We had too many boxes of gear to go on the small plane and one arrived at our hotel in the evening. Kelly's M.Sc. student Yuan-Yuan Xu came on a later flight and Zamara Fuentes, a student at the University of Puerto Rico Mayaguez who is doing her Ph.D. research on Anegada and will be our field guide, came even later, straight from San Juan.

Once we were all there, we went to a local supermarket and bought all our supplies (including water) for 6 people to last 10 days. Anegada has no large store and only limited water from a desalination plant, which is not potable. Our purchases were neatly packed in 13 boxes which will be delivered at the dock at 6 AM on Wednesday to go on our ferry to Anegada.

On Wednesday, we all took the fast ferry from Tortola to Anegada, a bumpy ride of about an hour. Unlike volcanic Tortola, which is mountainous, Anegada is a sandy island that is very flat. It has a single main road that goes around half of it and only about 200 permanent residents. Like all of the BVI, the language is English and US dollars are used as the currency for convenience. We picked up our 'rental vehicle', a beat up pick-up with benches in the truck-bed on loan from one of the locals, and drove to our cottage on the north side of Anegada.

Our cottage is comfortable with two bedrooms, a full kitchen, hot water and internet (well actually, we had to wait a day for the latter two). Our hydraulic coral drill has not passed customs and will arrive a few days late. However, we will not be deterred, sampling starts tomorrow!"

* * *

MARCH 14

Our hydraulic coral drill has not yet arrived and therefore Zamara, Yuan-Yuan, and Johan are going to take sediment cores for Zamara's Ph.D. research while Hali is going to check on the status of our shipment.

Zamara wants to take a series of cores, every 500 m along a straight line across the 2.5 km width of the island. This involves wading through Flamingo Pond, one of Anegada's large but shallow hypersaline ponds where seawater evaporates until the salinity is about 3-4 times the normal value. This causes a thick crust of gypsum to precipitate on the bottom, a reasonably solid surface to walk on. The gypsum is however covered by a thick layer of bacterial mats that can make it slippery and by strange colonies of salt-tolerant 'pipe cleaner' algae. We have to wear heavy shoes, because in sandals the sharp salt crystals and sediments would cut your skin.

The first core on the lake shore is a failure. Zamara and Johan sink knee-deep in about 50 cm of oozy mud, even though they are standing on a pallet, and the mud will not stay in the coring device. We have more success with the first two cores in the pond, although it is a balancing act with three people holding all the things we cannot set down in the extremely salty water. (see photo above)

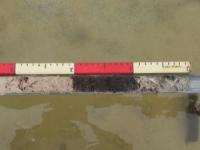

Zamara is looking for features in the core that may indicate the timing of the tsunami that swept across the entire island. In the second core you can see a layer of marine sediment on the left, then a dark layer of peat from a time when mangroves or other plants may have grown in this spot, and finally a layer of grey mud laid down in the anoxic hypersaline water. The third core in the lake also fails and we have to take a wedge of sediment with shovels.

Zamara is looking for features in the core that may indicate the timing of the tsunami that swept across the entire island. In the second core you can see a layer of marine sediment on the left, then a dark layer of peat from a time when mangroves or other plants may have grown in this spot, and finally a layer of grey mud laid down in the anoxic hypersaline water. The third core in the lake also fails and we have to take a wedge of sediment with shovels.

When we reach the other side of the lake, the shoreline is a checkerboard of mud-cracks. Actually, this is not mud at all, but a thick layer of Jello-like sugars that are secreted by the anaerobic bacteria. The blueish color on top are the active bacterial mats.

Our last sample is taken on land and instead of coring we dig a pit of 1 m x 1 m x 1 m. Unfortunately we hit the shallow aquifer and the pit fills with saltwater, so we take a core anyway. With some effort, we get a good recovery of about 70 cm.

After fighting our way through another 200 m of dense and prickly vegetation we hit the northern main road where we are picked up by Hali, who has exchanged our pickup truck for a larger one that will be able to hold the hydraulic drill. We are exhausted, but it was a successful day!

* * *

MARCH 15

Since we still do not have our hydraulic drill, chief scientist Hali decides that we should go prospecting for some of the coral heads that have been discovered during prior expeditions and that are marked on detailed areal photographs we have of the entire island.

We drive into an area that contains many coral heads, on a very rough road. In fact, this is not a real road, but a solid layer of Pleistocene reef that is weathered down until it looks like concrete. It quickly becomes too bumpy for our truck so we leave it behind and strike out on foot. We navigate by our GPS, but there are few landmarks, except low walls built in the 1800s out of limestone boulders by the first settlers of Anegada. The terrain is extremely rough and densely vegetated with many hazards (photo at right).

We drive into an area that contains many coral heads, on a very rough road. In fact, this is not a real road, but a solid layer of Pleistocene reef that is weathered down until it looks like concrete. It quickly becomes too bumpy for our truck so we leave it behind and strike out on foot. We navigate by our GPS, but there are few landmarks, except low walls built in the 1800s out of limestone boulders by the first settlers of Anegada. The terrain is extremely rough and densely vegetated with many hazards (photo at right).

The first coral head we find has been broken into pieces, probably by other scientists. We mark its location on our GPS as we do with every next find. After hours of roaming around and some lunch in the hot sun, we find what Hali is looking for: a coral head large enough to drill (below). This was picked up by the tsunami and deposited many hundreds of meters from the shore. It had been previously dated to be from around 940 AD (note that this is the age of the coral, not the time when the tsunami moved it).

Hali gets a phone call from the shipping agent with good news: the drill has cleared customs and will arrive on the afternoon ferry. We fight our way back to the road and the truck through the sea grapes and cacti. It is going to be a chore to carry the 150-lb drill in here later this week!

We look around in another, much more open area on the shore of a salt lake for a very large coral head called Big Mama I, but we don't find it and Hali forgot to bring the coordinates. We do find some smaller coral heads that are right next to the road, which will be perfect for a practice drill tomorrow.

We return home to clean ourselves up before we meet the afternoon ferry and pick up the drill. All parts arrive in good order, except one of the wheels has been knocked off the drill frame, which makes it even harder to move. Back at the cottage, Johan thus gets a chance to try out Hali's new tool set. After an hour of sweating, the tire is back on the mangled rim, the rim neatly hammered flat, and the whole thing attached to the drill frame again. We are ready for tomorrow!

* * *

MARCH 16

Everything is now ready for our first day of coral drilling, also due to the excellent efforts of our contacts at the Tortola Department of Disaster Management, Sharleen DaBreo, Alex Jeffrey, and Garymar Dé Rivera, and the wisdom of USGS geologist Brian Atwater, who is a world expert on all things tsunami and especially all things Anegada.

We return to the coral head that we found yesterday on the side of the road and set up the hydraulic drill. This involves positioning the truck, connecting the hydraulic engine to 50 ft of hydraulic hose, and the hose to the drilling tool, which is then fitted with a long core barrel. The barrel is a hollow metal pipe with a diamond edge that grinds a solid plug out of the coral head. It is also connected to a backpack pump that supplies water to the barrel for lubrication and cooling. Finally, we fill up the engine with (biodegradable!) hydraulic oil and we are ready to go.

We return to the coral head that we found yesterday on the side of the road and set up the hydraulic drill. This involves positioning the truck, connecting the hydraulic engine to 50 ft of hydraulic hose, and the hose to the drilling tool, which is then fitted with a long core barrel. The barrel is a hollow metal pipe with a diamond edge that grinds a solid plug out of the coral head. It is also connected to a backpack pump that supplies water to the barrel for lubrication and cooling. Finally, we fill up the engine with (biodegradable!) hydraulic oil and we are ready to go.

First we carefully dig away the sand around the coral head, so that coral expert Hali can determine the direction of growth. A coral head is a little like a thick bundle of calcium carbonate 'ropes', where each individual rope is created by a single coral polyp. The trick is to drill exactly along the length of these ropes, but instead of growing straight they are usually curved and twisted. It thus takes some time to determine where to start drilling and at what angle to aim the core barrel.

Johan lifts the 60-70 lb coral head on one side and we find it is right-side-up, so we can drill roughly vertically down from the top. It takes four people: one to operate the hydraulic engine, one to drill, one to hold the barrel in place as the hole is started and to pressurize the water pump, and one to hold and control the water supply. After about an hour we have drilled several small practice cores from the coral head, but then the drill stops working. We pack up and go back home.

Johan lifts the 60-70 lb coral head on one side and we find it is right-side-up, so we can drill roughly vertically down from the top. It takes four people: one to operate the hydraulic engine, one to drill, one to hold the barrel in place as the hole is started and to pressurize the water pump, and one to hold and control the water supply. After about an hour we have drilled several small practice cores from the coral head, but then the drill stops working. We pack up and go back home.

After a few hours of rest the drill seems to be working, so we go out once more to find Big Mama I, this time armed with the coordinates. We find the enormous coral head in the middle of a large salt flat that is relatively easy to reach from the road. Hali wants to drill it right away so we drag all the equipment out to the site, but the drill fails again. After a long time trying we give up and drag all the equipment back to the truck. We have our first coral cores but we are very disappointed that Big Mama has defeated us so far.

* * *

MARCH 17

We spend the morning at our cottage in frustration, trying to get the drill to work. We browse in manuals, make phone calls, and send e-mails, but it is difficult to get a hold of anyone on a Sunday. We come up with various theories, but nothing seems to explain all the symptoms we observe. Johan finally makes an adjustment to the trigger mechanism of the drill and this seems to do the trick: we are able to drill a core from a piece of coral we brought back from Soldier Point on Friday.

We are exhilarated, but it is too late to take the drill out into the field. Instead, Hali wants to do some coral prospecting around Loblolly Point, at walking distance from our cottage. On the way we stop at Flash of Beauty, a tiny restaurant on the beach, to ask if we can have dinner there tonight. The population of Anegada is so small that restaurants only open if they know people are coming for dinner and you have to order in advance. The owners then go out to catch your meal and everything is prepared from scratch.

Walking around Loblolly Point we find one coral head from our list, but Hali can tell it is too small for drilling. Hali returns to the cottage because she has to pick up Bob Halley, a carbonate geologist retired from the USGS in St. Petersburg, FL, who is arriving on the afternoon ferry to join our field team. Johan, Yuan-Yuan, and Zamara continue looking despite occasional rain squalls and find three more coral heads, but they are even smaller than the first one. We return to the cottage as well and on the way back we encounter a large land crab on the road (photo A). They are mostly nocturnal and you see their tracks in the sand everywhere.

Hali soon appears with Bob and after some catching up we all get ready for dinner. Bob is checking into a different hotel tomorrow and in the mean time he is spending the night on our couch and he has also brought some welcome supplies of fresh food. At the restaurant the table is already set for five on the outside patio; we are the only guests. Cook Monica, an Anegada resident originally from Trinidad, serves Johan curried conch with rice and the others each a huge spiny lobster (photo B). The food, weather, and company are all lovely and after dinner Monica entertains us with some local stories. We walk back along the beach in the dark. Today was not as productive as we had hoped, but we are confident that tomorrow will be better.

Hali soon appears with Bob and after some catching up we all get ready for dinner. Bob is checking into a different hotel tomorrow and in the mean time he is spending the night on our couch and he has also brought some welcome supplies of fresh food. At the restaurant the table is already set for five on the outside patio; we are the only guests. Cook Monica, an Anegada resident originally from Trinidad, serves Johan curried conch with rice and the others each a huge spiny lobster (photo B). The food, weather, and company are all lovely and after dinner Monica entertains us with some local stories. We walk back along the beach in the dark. Today was not as productive as we had hoped, but we are confident that tomorrow will be better.

* * *

MARCH 18

After breakfast we take Zamara to the morning ferry. She is going back to Puerto Rico to present a poster at the GSA meeting. Then Hali, Johan, Yuan-Yuan and Bob head to Big Mama I. For the second time we drag all the equipment out onto the salt flat, but now the hydraulic drill is working. It takes a bit of effort to keep it going: we develop a kind of ritual that involves running the hydraulic oil through a loop, or opening the trigger seal to relieve back-pressure, or attaching the drill directly to the hydraulic engine, or combinations of these. We are not entirely sure why it works, but it does. Bob also throws in some dancing and chanting for good measure.

After several hours of hard work we have drilled two perfect 3-inch cores. One from the top of the coral head to well below an unconformity, a small gap where the coral head stopped growing and then started again. The second goes from the top of the unconformity, which is exposed at the front of the coral head, all the way to the bottom. Victory! This is the main reason we traveled to Anegada. Hali tries to drill the first hole all the way to the bottom, using a smaller core barrel with an extension rod, but she retrieves nothing but rubble and peat. No matter, we got what we came for.

After packing everything back in the truck we return to the area where we drilled the practice cores on Saturday. Hali had spotted a good coral head she thinks might be Pleistocene in age and wants to drill a core from it, not for this study but maybe for a future project. Bob thinks the coral might be Holocene instead. Proper dating, using uranium isotope ratios, will eventually give the answer but some frosty beverages are already wagered on the outcome. We can drive the truck right next to the coral head and leave the hydraulic engine on the bed. The core is quickly drilled. We are getting good at this!

We drive to the ferry dock to pick up Edgardo Quiñones, an M.Sc. student who studies paleoclimate using corals, at the same university as Zamara. But first we stop on a lake shore off the southern main road to check out some coral heads that Bob knows about. One looks pretty good so we drive the truck onto the sand, roll out the hydraulic hoses, drill another core, and we're on the road again in time to meet Edgardo. He and Bob check into "Neptune's Treasure", a small hotel near the ferry dock. After that, we all go back to Loblolly Cottages where Edgardo and Bob cook an excellent pasta dinner. The two of them take the truck back to their hotel and we go to bed early. All the 'easy' coral heads have been drilled, so tomorrow we go deep into the brush at Soldier Point!

* * *

March 19

After breakfast, Hali, Johan, Yuan-Yuan, Bob, and Edgardo venture out to Soldier Point to drill three large coral heads we located there earlier. Our biggest problem is going to be cooling the drill, since we will not be near a source of water. We therefore fill the 4-Gl. reservoir of our backpack pump as well as 10 more 1-Gl. jugs with water at the cottage before we leave.

The road goes from concrete, to sand, to limestone, and Johan carefully inches forward as far as is safe, while Edgardo walks ahead of the truck to prevent it from falling into one of the many hidden sinkholes. Then we carry the equipment, including the 150-lb hydraulic engine and all the water, to the first site, directed by the waypoints marked on our GPS. We struggle 300 m along the road beyond where the truck can go and then 150 m into the bush, which takes a total of 2 hours and several trips. We become pretty badly scraped up, because the tsunami has thrown these boulders among dense and prickly vegetation, not onto an open salt flat like Big Mama I.

The road goes from concrete, to sand, to limestone, and Johan carefully inches forward as far as is safe, while Edgardo walks ahead of the truck to prevent it from falling into one of the many hidden sinkholes. Then we carry the equipment, including the 150-lb hydraulic engine and all the water, to the first site, directed by the waypoints marked on our GPS. We struggle 300 m along the road beyond where the truck can go and then 150 m into the bush, which takes a total of 2 hours and several trips. We become pretty badly scraped up, because the tsunami has thrown these boulders among dense and prickly vegetation, not onto an open salt flat like Big Mama I.

We drill several cores out of the first coral head, sometimes using pieces that have been previously broken off by other scientists probably to date the coral. An e-mail from the drill manufacturer has identified our problem as a leaky O-ring and although we have no spare part to fix it we now know how to keep the system going by occasionally draining excess hydraulic oil from behind the trigger.

It is still early when we are done, but we have run out of cooling water so further drilling will have to wait. However, to reduce tomorrow's workload we decide to carry the equipment an additional 150 m to the next site, where the other two coral heads are located close together. We will leave most of the equipment in the field overnight; it is so heavy and so far from the road that nobody is likely to steal it, but we do stack some pieces of limestone on top of the hydraulic engine to provide some protection from possible rain.

Hot and tired we hike back to the truck with our bounty of cores and the empty water jugs. We return to the cottage for dinner, a cool drink, and a much needed shower.

* * *

March 20

This morning the coral team goes back to Soldier Point to continue drilling there. We carry in a new supply of cooling water and find our equipment as we left it yesterday. The first coral head is broken into a number of pieces and Hali is able to obtain only a single usable core. The second coral head, just 50 meters or so from the first one, looks more promising but several attempts do not really yield the desired result: we retrieve a few short core sections but deeper into the coral we get only rubble mixed with peat. This indicates that water and soil or algae got into a pre-existing crack, which may have altered the chemistry of the coral skeleton and make it a less reliable record of past climate. Nevertheless, Hali will take the pieces back to the US, where careful microscopic inspection and spectroscopic analysis of the calcium carbonate material will give the final verdict.

Once we are done drilling, Bob tells us that the nearby beach contains a large coral 'rampart', deposited not by the tsunami but by recent hurricanes. Hali wants to take a look, because she may be able to find some small modern coral heads that she can take back to check her Sr/Ca temperature calibration. We fight another few hundred meters through the brush and climb the dune. Johan twists his ankle and Yuan-Yuan steps onto a dead barrel cactus whose spines go right through the sole of her shoe into her foot. While they take a break to recover, Hali, Bob, and Edgardo scour the beach for some well-preserved specimens of various coral species. Then we return to the drill site and begin the arduous task of carrying all our equipment back to the truck.

After some rest at home, Hali wants to drill thin cores from the modern specimens, so that these samples look less like live coral. This will prevent confiscation by customs officers at the airport who cannot always tell the difference. Prior to drilling, we immobilize each coral head by burying it in the sand outside our cottage. Our work is made a little difficult by a feisty crab who has decided to use our cardboard pad for shade and is willing to take it by force. When we have finished, we disassemble the drill and drain the fuel and the hydraulic fluid from the engine, so that they can be packed for shipping. The coral cores are wrapped in bundled pieces of PVC pipe that will go back with us on the plane. Now, the only thing left to be done is collecting seawater samples for measurements of Sr/Ca ratios. More about this tomorrow.

After some rest at home, Hali wants to drill thin cores from the modern specimens, so that these samples look less like live coral. This will prevent confiscation by customs officers at the airport who cannot always tell the difference. Prior to drilling, we immobilize each coral head by burying it in the sand outside our cottage. Our work is made a little difficult by a feisty crab who has decided to use our cardboard pad for shade and is willing to take it by force. When we have finished, we disassemble the drill and drain the fuel and the hydraulic fluid from the engine, so that they can be packed for shipping. The coral cores are wrapped in bundled pieces of PVC pipe that will go back with us on the plane. Now, the only thing left to be done is collecting seawater samples for measurements of Sr/Ca ratios. More about this tomorrow.

* * *

March 21

Today we are collecting seawater samples from above the coral reef just outside our cottage (above). The coral cores that Hali has collected will be analyzed for ratios of strontium (Sr) and calcium (Ca). The coral takes up these elements from seawater in a ratio that changes with the ambient temperature.

By measuring the Sr/Ca ratio of the coral skeleton, Hali can determine the temperature of the seawater at the time the coral was growing, in order to learn about past climate. However, this only works if the Sr/Ca ratio of the seawater itself is constant with respect to both location and time. This is generally assumed, but it has mainly been tested in the open ocean and there are indications that it may not be true in the coastal zone, where the coral reefs are. Our seawater samples will be used to settle this issue.

We started with a 24-hour time series yesterday at 6 p.m., wading about knee-deep into the surf from the beach. Every 3 hours, seawater is collected from just below the surface with a plastic syringe and then filtered into acid-washed 60 mL bottles that we brought with us. The bottles are packed into labeled Ziploc bags, which we will take back to CBL for analysis. Johan, the trace metal expert, trained Yuan-Yuan and Edgardo, who then took the 6 p.m. and 9 p.m. samples. Johan and Hali do the night shift (midnight and 3 a.m.) and this morning the others take turns until the time series is complete at 6 p.m.

In addition, Hali has designed an experiment to determine the spatial variability of seawater Sr/Ca. Sampling from a bright pink sea kayak that Bob and Edgardo have borrowed from their hotel, we sample a grid of four points along the beach at three different distances from the shore, one very close, one near the far edge of the reef (see the line of surf in the pictures), and one in between.

Yuan-Yuan and Johan go out first, but there is a fierce wind and alongshore current and while Yuan-Yuan takes the samples, Johan has to continuously paddle as hard as he can, just to stay in place, using visual reference points on the beach. After 90 minutes only half the points have been sampled but Johan is exhausted and needs a rest.

After lunch, Hali and Johan go out again to finish the grid. Although we take waypoints, it is hard to judge your relative position on the water. Nonetheless, when we check the final GPS map the spatial distribution of points looks pretty good. In the meantime, everyone not involved in seawater sampling is busy packing up samples, equipment, personal belongings, and the leftover food and water.

Tomorrow is our last day and we are leaving early!

* * *

March 22

When Bob and Edgardo went back to their hotel last night they took as much of the equipment as they could fit into the truck, including the sea kayak. Very early this morning they drop everything at the ferry dock and Edgardo stays there to guard it.

Bob picks up Hali, Yuan-Yuan, and Johan with the rest of their luggage and the remaining food at Loblolly Cottages, which has been our home for the past 10 days. They help Bob to move the food and his luggage to a different apartment, because he is staying on Anegada to help another team of scientists. Then he drives us to the dock where we board the fast ferry and supervise the loading of our gear. The ocean has calmed considerably since we arrived on Anegada and the 1-hour trip to Tortola is now a lot more comfortable.

Bob picks up Hali, Yuan-Yuan, and Johan with the rest of their luggage and the remaining food at Loblolly Cottages, which has been our home for the past 10 days. They help Bob to move the food and his luggage to a different apartment, because he is staying on Anegada to help another team of scientists. Then he drives us to the dock where we board the fast ferry and supervise the loading of our gear. The ocean has calmed considerably since we arrived on Anegada and the 1-hour trip to Tortola is now a lot more comfortable.

In Road Town, Hali leaves Johan, Edgardo, and Yuan-Yuan out on the street with all the gear, while she goes to the Department of Disaster Management where she is scheduled to give a seminar on the purpose and significance of our fieldwork, to ensure that we may be invited to return. In the mean time, Johan checks into a new hotel at walking distance from the ferry dock and then he and Edgardo take several trips to carry the gear to the room, which thankfully is on the ground floor. Yuan-Yuan keeps an eye on the rapidly shrinking pile. When this is done, Edgardo and Yuan-Yuan rent a taxi to the airport; they are flying home today. Johan stays behind and takes a nap to recover from transferring 500 lbs of stuff in the hot sun in less than 30 minutes.

In the afternoon Johan meets Hali in town and they are joined for lunch by three employees from the Department of Disaster Management, by tsunami expert Brian Atwater, by Zamara who is back from the GSA meeting, and by Dr. Michaela Spiske, a postdoctoral scholar who studies tsunami deposits at the University of Münster in Germany. The latter three will go to Anegada later today to continue geological fieldwork (not focused on corals) with Bob Halley. Several of us order the local salt fish (cod) with 'provisions', a traditional mixture of plantains, yams, and cassava dumplings. There is animated discussion about the chance of another tsunami striking Anegada at some time in the near future, and its possible effect. After lunch Johan and Hali get a ride back to the hotel from Alex Jeffrey and he and Hali then take the equipment to the airport customs office for shipment back to the US. Tomorrow, Johan and Hali will move to the west side of Tortola for a few days of well-deserved vacation. Our field expedition is officially over!

Greetings from the 2013 Anegada coral drilling team. Hali thanks the National Science Foundation for funding and with their continued support we hope to be back for more next year!