Meet the Double-Crested Cormorant (Nannopterum auritum)

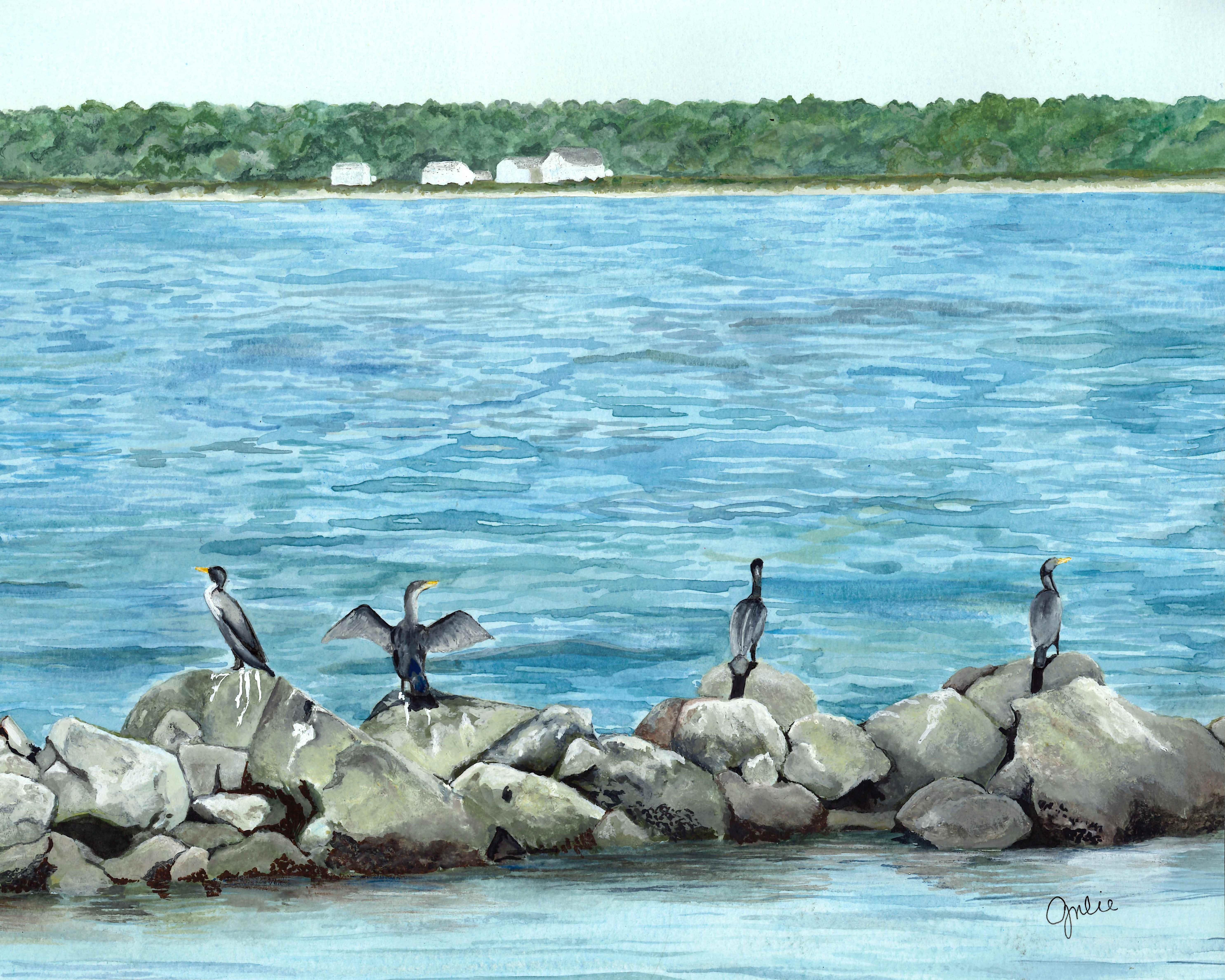

If you've spent any time near water around the Chesapeake Bay, or really almost any coastline of the USA and beyond, you've likely seen large black birds perched on rock, piers, or bollards with their wings half-spread to dry. This is the double-crested cormorant (Nannopterum auritum), a large and arguably gangly-looking common waterbird of our local waters, and the most widely distributed of all the cormorants. From a distance, these dark birds may look similar to migrating geese, though they travel quietly rather than raucously. But up close, they sport splashes of color: orange-yellow facial skin, brilliant turquoise eyes, and a bright blue inner mouth. During breeding season, adults sport paired tufts of feathers, which are the "double crests" that give them their name, though these ornamental plumes are subtle rarely visible. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology describes their appearance as “like a combination of a goose and a loon”.

The cormorant's most recognizable behavior, standing in the sun drying out their wings in the wind, is a result of evolutionary trade-offs that enable this bird to be both effective at flight and hunting underwater. Wet feathers impede flying and provide poor insulation, but preened feathers well coated with oil, like those of ducks and geese, make deep diving in the water to catch fish a very difficult challenge. The evolution of cormorants has landed on a successful strategy in which these birds do not waterproof their feathers with oil, enabling them to dive deeply in water and pursue prey. But then, after hunting, they must stand with wings outstretched to dry before they can fly again. This may seem an awkward requirement, but their widespread distribution and rapid population growth in recent decades is testament to the success of this strategy.

Double-crested cormorants are highly adaptable and found across nearly every aquatic habitat in North America, from rocky northern coastlines to southern mangrove swamps, inland lakes to coastal estuaries. They're colonial nesters, sometimes sharing nesting sites with herons and other waterbirds, and they build bulky stick nests that frequently incorporate found materials, like fishing nets, plastic debris, and other even less appetizing materials. Males court females with elaborate aquatic displays, that includes splashing with their wings, darting in zigzags through the water, and diving to bring up pieces of vegetation.

The Chesapeake Bay has long been an important stopover for migrating cormorants traveling between southern wintering grounds along the U.S. coast and northern breeding colonies in New England, the Canadian Maritimes, including Newfoundland. Peak migration periods occur in spring when they’re heading north (March through May) and fall when they’re heading south (August through November), when the Bay's fish populations provide plentiful fuel for their journeys. The birds do not all breed at once at a colony, and this staggered nesting over a couple of months means young are at various stages of development at any given time, with families not migrating together, creating the prolonged migration periods we observe.

In the past, double-crested cormorants were generally all transient visitors en route to overwintering grounds just south of here or summer breeding grounds just north of here. What's changed in recent decades is that breeding colonies have begun to increase in the Chesapeake Bay region. The first confirmed double-crested cormorant nest in the Chesapeake Bay region was discovered in 1978 on the James River, with just 6 breeding pairs.

This colonization was part of a remarkable continental recovery story. Throughout the mid-20th century, cormorant populations plummeted due to widespread persecution (people routinely destroyed eggs at nesting colonies, believing the birds competed with fisheries) and later from DDT contamination, which caused brittle eggshells and chick deformities. After DDT was banned in 1972 and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act provided legal protection, cormorant populations rebounded dramatically and expanded their range. In the Chesapeake, this recovery has been explosive: by 1993, surveys conducted by Center for Conservation Biology documented 354 breeding pairs; by 2013, that number had grown to over 5,000 pairs across 12 colonies. Though they consume fish prolifically, they primarily feed on bottom-dwellers like oyster toadfish and hogchoker, and have not been found to significantly depress fisheries populations, though they're managed to prevent nuisance nesting on structures like the Bay Bridge where they could become hazards. From occasional migrants to permanent residents, double-crested cormorants have written themselves into the ecological story of the modern Chesapeake Bay.

Looking for More Information?

Center for Conservation Biology. (2013, December 3). Chesapeake Bay cormorants continue steep ascent. https://ccbbirds.org/2013/12/03/chesapeake-bay-cormorants-continue-steep-ascent/

Hendricks, M. (2019, June 26). On the wing. Chesapeake Bay Magazine. https://www.chesapeakebaymagazine.com/on-the-wing/

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Double-crested Cormorant. All About Birds. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Double-crested_Cormorant/

National Audubon Society. Double-crested Cormorant. Audubon Field Guide. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/double-crested-cormorant

Chesapeake Bay Program. Double-crested Cormorant. Field Guide. https://www.chesapeakebay.net/discover/field-guide/entry/double-crested-cormorant

Williams, John Page, Jr. "March: Cormorants Migrating." Chesapeake Almanac, Chesapeake Bay Foundation, 2021. https://www.cbf.org/resources/march-cormorants-migrating-podcast/