Dinophysis: The Chloroplast Thief (May 2025)

by Sairah Malkin

A Microscopic Beauty with a Dark Secret

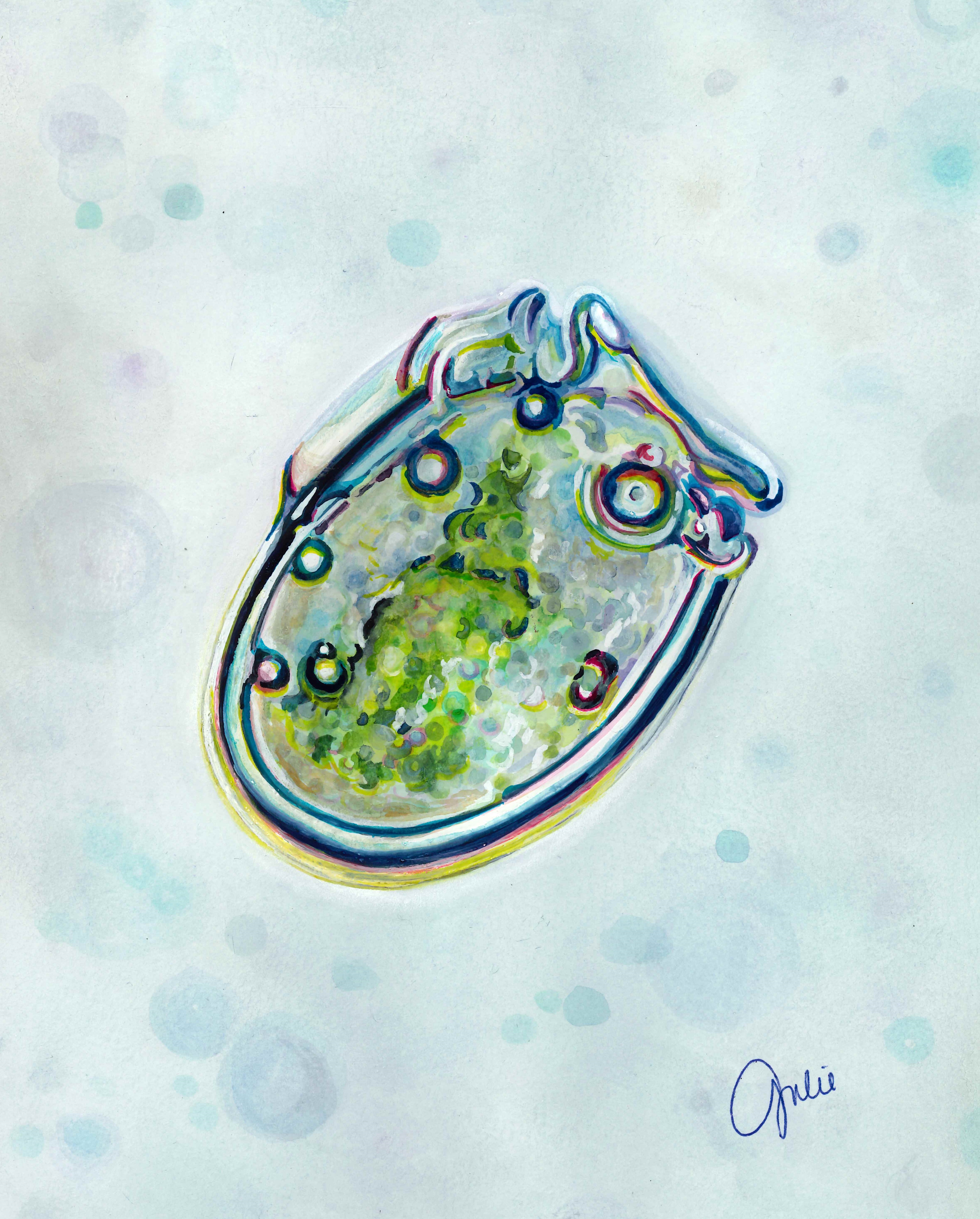

Every week at the PhytoChop Observatory, our team peers into the hidden world of marine microbes through our microscopes, and collects water samples for DNA analysis. This past spring, Julie Trommatter, our resident watercolor artist and senior oyster hatchery staff, was captivated by what she saw. “This is among my favorite looking phytoplankton,” she said while observing the distinctive and fast swimming organism called Dinophysis.

It's easy to see why this little cell might have fans. Dinophysis is a dinoflagellate with two whip-like appendages called flagella for locomotion, and sports a distinctive crown on its top and fin at its side. If you could watch one slow for a moment, you’d notice it’s packed with green patches (chloroplasts for photosynthesis) as well as bubble-like globs which are actually used for digesting ... prey?

A Multi-Level Chloroplast Heist

Most organisms follow simple rules: plants make their own food through photosynthesis, while animals forage or hunt for their meals. Dinophysis, however, makes its own rules. It's a master thief that steals the very machinery of photosynthesis from its victims.

Here's how this microscopic heist works: Dinophysis hunts down a specific prey, a ciliate called Mesodinium, which looks like a microscopic red ball covered with fine hair. But Mesodinium isn't innocent either; it has already stolen its own photosynthetic equipment by eating even smaller phytoplankton, such as Teleaulax, a type of cryptophyte. When Dinophysis captures and consumes Mesodinium, it's essentially stealing stolen goods, making it the top criminal in a three-level pyramid of chloroplast theft. (Scientists call this "kleptoplasty", a.k.a. chloroplast theft, and this dual plant-animal lifestyle "mixotrophy.")

Remarkably, these hijacked solar panels actually work. Once inside Dinophysis, the stolen chloroplasts function for months, allowing our diminutive thief to harness sunlight while also hunting for its next meal. It's like having a car that runs on both gasoline and solar power – a highly efficient strategy.

Terrible Nature

The name Dinophysis comes from Greek words meaning "terrible or fearsome nature", a name that hints at its darker side. While only about 12 out of the 100 or so described Dinophysis species produce toxins, those that do pose serious problems for humans.

The trouble starts when shellfish like mussels and oysters filter-feed on Dinophysis, concentrating toxins in their tissues. Even when Dinophysis is present in relatively small numbers, sometimes as few as several hundred cells in a liter of water, toxin-producing species can make shellfish dangerous to eat. People who consume contaminated shellfish can develop Diarrhetic Shellfish Poisoning (DSP), experiencing severe stomach problems that, while rarely fatal, can be extremely unpleasant.

Importantly though, not all species or strains produce toxins, and even among those that can, toxin production varies significantly with environmental conditions like temperature, nutrients, and prey availability. These factors are not yet fully understood. The threat of DSP was first recognized in Japan during the late 1970s when people became ill after eating contaminated mussels and scallops. Today, toxins from Dinophysis are a leading cause of shellfish harvesting closures in Europe, Japan, and Chile.

Dinophysis in Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay has its own history with Dinophysis, though it rarely lives up to its name of “fearsome nature”. Several species of Dinophysis call these waters home, where they are frequently observed in abundance, and likely play an important role sustaining the Bay’s food webs. They have rarely been observed to cause problems through toxin production. One exception was a 2002 bloom of Dinophysis acuminata in the Potomac River that triggered the first and only precautionary closure of Chesapeake Bay shellfish harvesting due to a toxic algae species. Fortunately, testing found no significant toxin accumulation in local oysters and the closure was lifted.

Nevertheless, scientists have identified several harmful algal bloom species that were once rare visitors but are now increasingly becoming regular residents in the Chesapeake Bay. This rogues' gallery includes Dinophysis acuminata alongside other disruptive dinoflagellates: Alexandrium monilatum, Karlodinium veneficum, Margalefidinium polykrikoides, and Prorocentrum minimum. Each brings its own brand of potential havoc, with some species potentially stressing adult oysters or disrupting oyster larval development, while others potentially threaten human health through contaminated shellfish. While Chesapeake Bay's Dinophysis populations appear relatively benign compared to those in other regions, we are reminded that there remains a need to understand what conditions drive toxin production and to monitor whether shifting environmental conditions create conditions that favor more dangerous blooms in the future.

Looking for More Information?

Jiang, H., Kulis, D.M., Brosnahan, M.L, and D. M. Anderson. 2018. Behavioral and mechanistic characteristics of the predator-prey interaction between the dinoflagellate Dinophysis acuminata and the ciliate Mesodinium rubrum. Harmful Algae 77: 43-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2018.06.007.

Moeller, H.V., and M.D. Johnson 2023. Mesodinium. Current Biology 33: R249-R250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.02.015.

Reguera, B., Riobó, P., Rodríguez, F., Díaz, P., Pizarro, G., Paz, B., and J. Blanco. 2014. Dinophysis Toxins: Causative Organisms, Distribution and Fate in Shellfish. Marine Drugs. 12(1): 394-461. http://doi.org/10.3390/md12010394

Stoecker, D.K., Hansen, P.J., Caron, D.A., and A. 2017. Mitra Mixotrophy in the Marine Plankton. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 9: 311–35 doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-010816-060617

Wolny JL, Tomlinson MC, Schollaert Uz S, Egerton TA, McKay JR, Meredith A, Reece KS, Scott GP and Stumpf RP. 2020. Current and Future Remote Sensing of Harmful Algal Blooms in the Chesapeake Bay to Support the Shellfish Industry. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:337. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00337

U.S. National Office for Harmful Algal Blooms: https://hab.whoi.edu/species/species-by-name/dinophysis/#:~:text=Morphology%20&%20Ecology,ecosystem%20in%20the%20water%20column.